Why are there Researchers?

Or: what is the point of the work that I do?

When I was in grad school and for the first part of my postdoc, I would almost proudly disclaim practical applications of the mathematics research I do.

My PhD work and subsequent research takes place mostly in the subfield of so-called "pure" mathematics called geometric group theory. A "group" to a mathematician, is an algebraic object that captures in an abstract way some kind of symmetry. I like to point out that the collection of ways of rearranging a Rubik's cube, for instance, forms a group, but that for the mathematician, the Rubik's cube itself is not core to the group, which has an existence all its own.

Geometric group theory means I use tools of geometry (shapes, spaces, distances, rigid motions) to study symmetry. It's like saying "hey, wait a minute, the Rubik's cube is useful, gimme that back I wanna use it to understand this thing."

Groups and geometry do have practical applications, of course. Understanding symmetries is important, for instance, in chemistry when studying molecules, crystal structures and so forth. Einsteinian astrophysics makes heavy use of the modern techniques of "differential" geometry to understand the shape of space. The fantastic number of symmetries of finite graphs makes enumerating them a slow problem. The matrix methods of linear algebra all make heavy (if implicit) use of concepts and techniques from group theory, many of which were likely developed in tandem with linear algebra. Lately I've been investigating symmetries of Boolean algebras, which are important in (digital) electrical engineering and computer science.

But, like, the focuses of geometric group theory are often pretty far removed from immediate application. My thesis is related to the group "of outer automorphisms of a free group" which involves a careful analysis of graphs, but in a way that is in my experience unlikely to resonate much with my friends who come across graphs in a computer science context. The Boolean algebras and groups I am most interested in are all infinite.

My answer to the question was in many ways a defensive acknowledgment of this, coupled with a desire to control something that ultimately is always completely out of my hands: namely, that my work not be used for purposes I find repugnant.

That desire is not entirely academic! A minority of researchers in my field somewhat regularly collaborate with or go to work for security agencies like the NSA in the US or GCHQ and MI6 in the UK. The secrecy that surrounds these agencies and regular scandals about civilians inappropriately targeted for espionage is not part of my ideal world, although I can grant that I neither see nor understand well all of the roles that secrecy and espionage plays in contemporary society.

Why ask the question?

Amusingly recently it occurred to me that when people ask me about applications of the research that I do, they are usually not asking me to justify my or my profession's existence.

And it is a fair question! An answer can help contextualize my interests by putting my work in relationship to something closer to the asker's life. Additionally, if it transpires that I collaborate with people who are not also academics working in research mathematics, the question is an opportunity to learn that.

Further afield, the question also verges on questions like:

- What got you interested in this?

- What is cool about it to you?

- What are you hoping to accomplish with your work?

- What does doing the work feel like?

- What does a day of that aspect of work look like?

Why not answer it?

There's a beautiful article by the late Bill Thurston titled "On Proof and Progress in Mathematics" whose themes are pretty closely related to this post, and which is accessible to a non-mathematician.

Thurston was one of the most impactful mathematicians of the 20th century. Ideas and questions initially popularized by Thurston are tied up in, for example, Perelman's resolution of the Poincaré Conjecture almost 100 years after it was posed, and Ian Agol's 2016 Breakthrough Prize resolving two conjectures of Thurston. He begins his article by asking the below question with about as much force as one can do without including a gif.

I like his answer quite a bit:

[W]hat we are doing is finding ways for people to understand and think about mathematics.

Put another way, a mathematician is someone who advances human understanding of mathematics. I'll come back to this point at length later, since it winds up being deeply involved in my answer to the questions above.

Thurston wrote "On Proof and Progress in Mathematics" in response to an article by Jaffe and Quinn whose abstract asks, "Is speculative mathematics dangerous?" Jaffe and Quinn discuss the role that "credit" for first proving a theorem plays in mathematics.

This role is pretty pervasive! Many journals in mathematics want to publish only original results, and although simultaneous discoveries of theorems are common (as are rediscoveries by researchers not connected with the original field), they come with a certain amount of anxiety. My first published paper, for instance, has four authors because as two groups of two we proved a similar theorem statement and then decided to write one paper combining our techniques and results. I felt a certain amount of pressure to work faster once the existence of the other group working on the same problem became known to me, and my PhD advisor had many thoughts—presumably from many many experiences—about the optics of various configurations of the final paper.

Like Thurston, I think that the emphasis on theorem-credits has a net negative effect on the field, although I suppose that as a way of making quantifiable the productivity and impact of a researcher on their field, one could very easily do worse.

The Purpose of Researchers

In fact, I'd argue that novelty of results is actually somewhat orthogonal to progress in "human understanding of mathematics". And that math research that remains useful only within mathematics often long after publication or even the death of the authors still serves a useful purpose to society more broadly.

Obviously relying too heavily on a suspected etymology of a word in one language is an easy mistake, but I do think the "re-" in research is useful here. One important facet of research (I suspect generally) is assimilation and digestion of previous work.

Most readers of a math paper—at least, in my guess at those who are researchers—are not reading with the purpose of finding reasons for believing the theorem. Rather, I am usually trying to pick up the ways of thinking the author uses for their problem in the hopes that it will be useful for approaching my somewhat related problem.

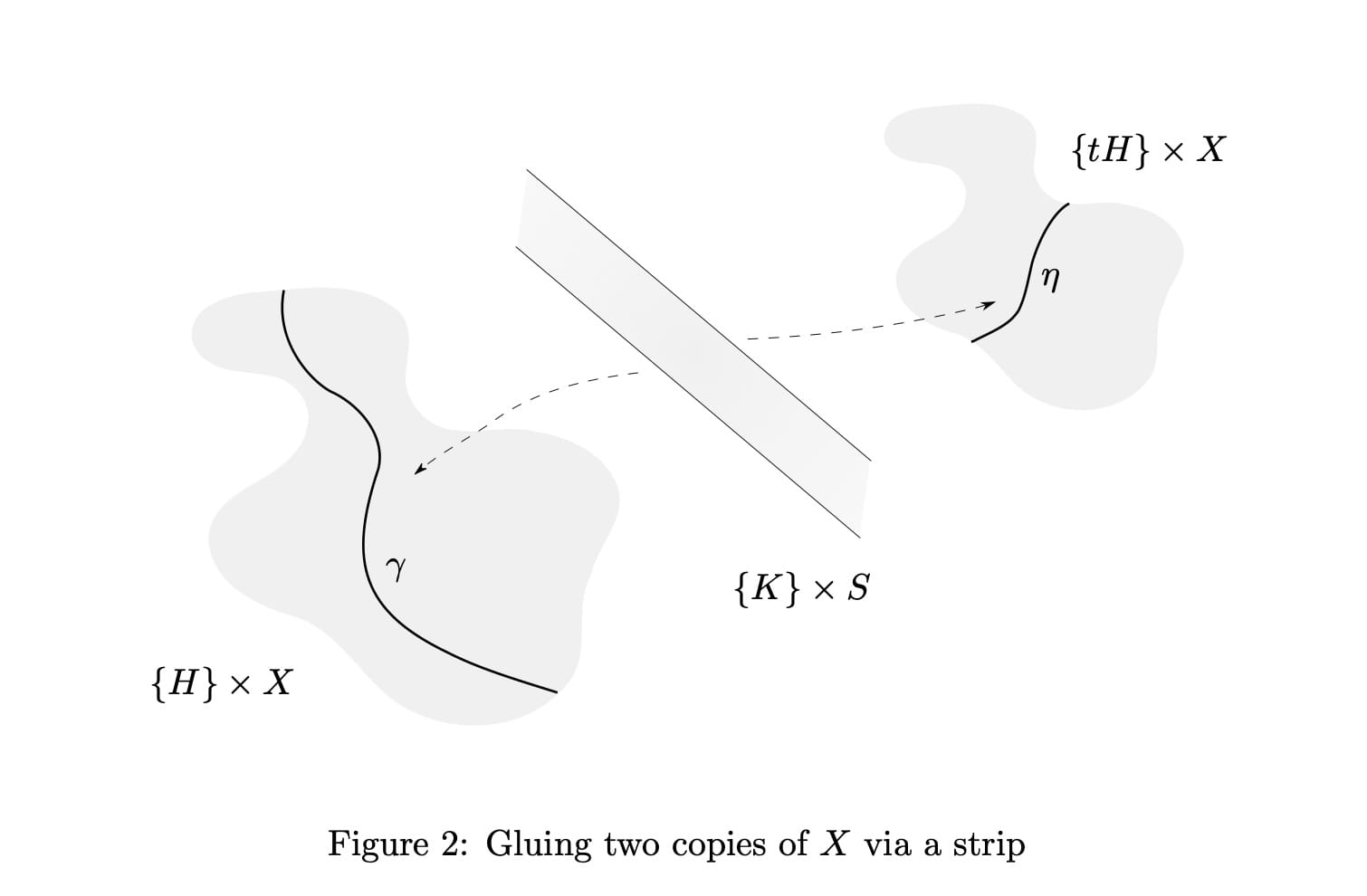

For my first written paper (which is maybe confusingly my 6th by publication date), for example, I was studying (at the suggestion of my PhD advisor) a paper by Peter Samuelson which contains, to date, my favorite application of the Intermediate Value Theorem. My initial problem space was a good deal more rigid than his, but from his paper I learned the importance of a gluing theorem of Bridson and Haefliger and how to think about candidate geometries for my situation.

With some well-disguised exasperation in her voice, I remember, my advisor asked me to "just understand this single case: is it or is it not CAT(0)?" (That's a geometric condition that involves "curvature" of a space in analogy with the Einsteinian statement that spacetime is curved. The name is the combination of an initialism of three 20th century mathematicians and a real parameter whose most interesting values are -1, 0, and 1.) In those days, I worked part time helping out in the math department office, and I remember figuring out that in this particular example, there was a constraint forcing a pair of lines to intersect at a right angle, but that if that constraint was satisfied, then suddenly I could induct and generalize to answer my advisor's question (and infinitely many variations of it) with a resounding "yes!"

Knowledge Rusts

Without someone like me to come along and read Samuelson's paper, the ideas within it will eventually corrode. Many math papers written before, say, 1950, are already often quite difficult to understand as compared with contemporary work—not really always because of the content, per se, but because the conventions of writing and notation as well as what is and isn't readily available as shared mathematical context has shifted enough.

Although my first written paper and Samuelson's may never become a part of the canon of mathematics or impact neighboring fields, both of these papers did solidify for me the role of core mathematical ideas like the Intermediate Value Theorem, the characterization of rectangles as those Euclidean quadrilaterals whose diagonals have the same length, and the Euclidean geometry fact that a straight line and a circle meet at most twice.

In other words, the work of research has as a valuable byproduct the advancing of my understanding (and hopefully others, in my exposition, lecturing and teaching work) of the core of mathematics.

This is important work indeed. Although society might not need geometric group theory, it certainly needs people who understand linear algebra deeply. Already we see researchers in other fields occasionally rediscover 2000-year-old insights behind the development of calculus. Arguably in a society where the division of labor is so advanced, such events are somewhat unavoidable.

Caretaking Knowledge is Valuable Work

What is avoidable and to be avoided is letting whole fields of human knowledge languish and die. In some ways, for instance, public funding of art in the United States is still reeling from the NEA having its budget halved in the 90s.

If mathematics research, or historians, or artists were to go completely unfunded and their work unpaid, mathematics, history and art would not go away. These are core aspects of human life. But the loss of useful and usable work would be felt.

My book club this month is reading Everything for Everyone: An Oral History of the New York Commune, 2052-2072, a fanciful "oral history" of a possible future where after 25 years of gleefully described horrific disasters of war, famine, climate change and disease, a sometimes cloyingly pat syndicalist utopia becomes the new world order (except in Australia, apparently). The authors, both academics themselves, cheer in particular the death of the academy as we know it.

I can empathize: the work (as in the job) of knowledge creation and education is often both extremely precarious and can feel very cutthroat. At the same time, I know that more than anything, the question "am I doing anything important to earn my daily bread?" can feel despairingly difficult to answer. The authors describe some significant changes that have taken place in the work of child-raising (and birthing), but the questions of education and preservation of knowledge are all but skirted.

Believably, one might imagine in the world of Everything for Everyone, knowledge and education take on a much more pragmatic character; everyone knowing enough to do what must be done for one's role in the commune, and anything else being effectively leisure for all but a tiny fraction of people. The authors "interview" a historian whose characterization is not dissimilar to The Dispossessed's Shevek: someone who doesn't really fit into the new world order, in part by virtue of being a bit too taken with knowledge.

The authors of Everything for Everyone focus on what is gained by this shift: making long distance earth or space travel more environmentally sustainable and less resource-intensive can more easily be the aim of work that does not need to satisfy a profit motive. But I think Le Guin is right to depict the world of Anarres in The Dispossessed as a society that has in some ways regressed in its knowledge.

So, here is my current understanding of what I do:

The purpose of research mathematics as part of the division of labor is in part tending to the garden of human knowledge of mathematics. In my teaching, I expose students to the habits and techniques of mathematical thought. Although I have some insight into where these techniques might be put to use, discovering those uses is actually literally not my job—it is my students's job to make use of their knowledge in the work that they do.

That gardening is not just keeping the lights on and pulling out weeds. By working to synthesize and understand the work of other mathematicians, I often (at regular but ultimately somewhat random intervals) have insights of my own. It is my job to communicate those insights to the audience that can make use of them. Most frequently that audience is made up primarily of other mathematicians, since the division of labor is certainly pretty well advanced.

You Don't "License" Mathematics

Several months ago in my Discord, an acquaintance who was particularly taken with LLMs at the time took one or more of my research papers to feed to ChatGPT or whatever it was. He wanted to demonstrate to me that it could be a useful tool for my research. I wasn't really convinced. (I'm still not particularly interested in or motivated to use LLMs for anything at all, although I'm certainly willing to change my mind.)

Nearly everyone in my Discord was surprised that I didn't find this use of my work to be a violation. Many of us in there are artists and are keenly aware of the ways that LLMs may be used to plagiarize or casualize the work of artists. On the contrary, I found this use of my work to be well within the spirit and letter of the ways I make my work accessible.

I'm grateful that my employment structure does not require me to make a profit from selling math papers, and that my university is frequently able to shoulder 100% of the costs associated with distributing my published work Open Access, without paywalls, to be read by anyone, even an LLM. One of the most valuable commons in mathematics and science, the arXiv, hosts almost 100% of preprints in my field.

Would a world like Anarres or the New York of Everything for Everyone with less advanced division of labor and a kinder approach to the problem of human survival be preferable? Almost surely. Would such a world have a culture significantly poorer for advanced mathematics, art, and any number of areas of human endeavor? I think this is also almost certain and would be something to genuinely mourn, not crow about.

Do we deserve a better view of the future than "well the next 25 years will be horrendous and then everything will collapse into a vindictive but ultimately liberatory world commune"? Yes, come on, dream bigger, dream happier, dream more human.