The Sounds of Japanese

This is the first in a series of posts about Japanese. I've been learning Japanese on and off since I was maybe 11. I'm not as fluent as I'd like to be (although maybe my goal of parity in skill level between English and Japanese is a bit lofty), and I'm certainly not an expert, but I figure I have maybe some interesting things to share. If you have feedback or want to point out an error, please do—I'm learning after all, and I'm sure that will help.

The sounds of Japanese were what I learned first. I remember reading books and articles on foreign language acquisition that claimed that your brain loses the phonemes (sound units of speech) of languages that you don't use, with some research claiming that this loss starts at puberty. I remember having a sense then that I was doing a task that future me would thank me for—and I do! But, while I'm glad to have a longtime knowledge of the sounds of Japanese, I doubt that it's ever too late to try and pick up new sounds.

This post will focus basically entirely on sound and not much at all on writing, words or grammar. I'll talk a little bit about pitch and intonation at the end, as well as "katakana English," which is a skill you could probably walk away with today.

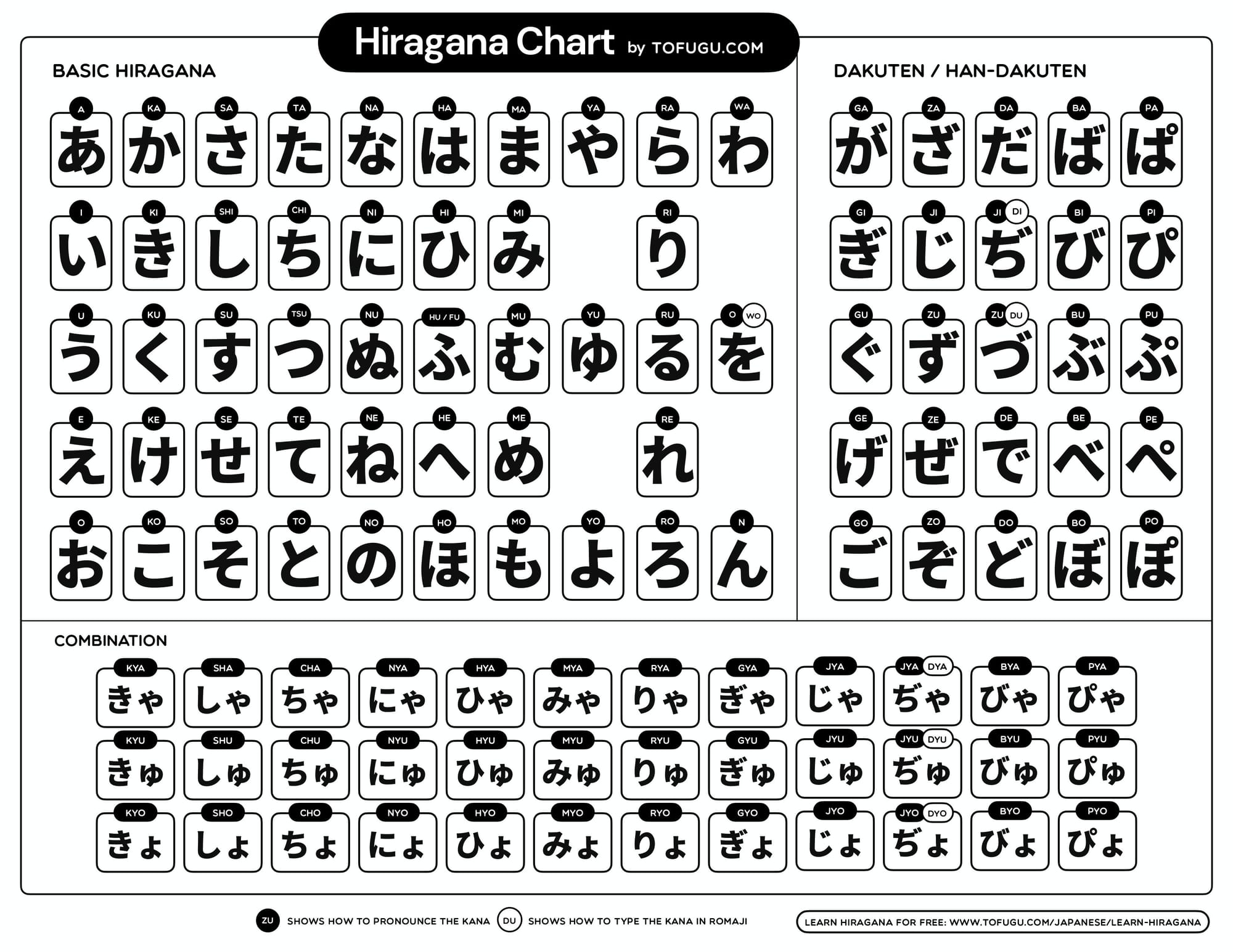

Here are (basically) all the sounds of Japanese in one chart. We'll talk about the writing later. From the perspective of a native English speaker, they don't present a huge challenge; I would say really between one and three consonants are a little tricky, and the vowels are mostly straightforward.

Let's make sense of the chart. Look at the "Basic Hiragana" section in the upper left. Notice that different symbols in the same row share a vowel sound. The vowels are arranged "a", "i", "u", "e", "o", which is standard for Japanese (if I knew why this order and not for example English's "a" "e" "i" "o" "u", I've forgotten). Different symbols in the same column have the same consonant sound at the front—which for the first column is no consonant at all. The last column is a bit of an exception—some other charts would put "wa" and "wo" in their usual places and then have an extra column just for "n". It's interesting to note that the "y" column has no "yi" or "ye" sounds.

So: basic Japanese sounds are (with the exception of that ん "n" on the lower right of this "Basic Hiragana" section) all a vowel optionally preceded by a consonant. The rest of the chart matches this pattenr; the "dakuten" part (addition of those two dots) changes essentially the consonant from what a linguist would call an unvoiced consonant ("k", "t", "s") to a voiced version of that consonant ("g", "d", "z"). The "handakuten" refers to the far right column in this part of the chart, the addition of the little circle has the effect on sound of changing "h" into "p".

The bottom row takes a regular hiragana (from the "i" row) and adds a smaller version of a hiragana from the "y" column to create a combo sound, like "kya" as opposed to "ki-ya".

We'll come back to pronouncing these sounds in a second. The little roman letters above each symbol are from one system of romanizing Japanese called Hepburn Romanization after the author of an 1860s Japanese–English dictionary who popularized the system. Other systems exist, but Hepburn's works particularly well and is so popular (I believe) because it is for the most part systematic but makes exceptions for cases where a different English consonant might better approximate the sound.

Morae

First, though, I want to notice that the hiragana symbols actually give us more info about Japanese: when written in hiragana (or katakana, more about which later), each symbol records one unit of time. These units are called mora, which is a Latin word. In Japanese they're called 拍 ("haku") which means something like "beat".

Each mora should receive (ideally) the same length of time when pronounced. This means that the length of a vowel—and truly length, not in the way English describes vowels as "long" or "short"—can be the distinguishing difference between two words. For example, お祖父さん (ojiisan, "grandpa") versus 叔父さん (ojisan, "uncle"[1]). Most vowels in Japanese are either one or two mora, but longer combinations exist. In a sentence where a queen is the object of the sentence, you might see 女王を, which gives an "o" sound a total of four morae!

Actually, both of the words お祖父さん and 叔父さん can be used without implying a kinship relation between the man you're referring to and anyone else in the conversation.

In this usage the former ojiisan simply means something like "this old man," while ojisan would just mean "this adult man," possibly with the valence of "who is older than me." That latter usage actually shows up in a similar fashion in AAVE as the word "unc." ↩︎

YouTube's algorithm happened to give me a great video illustrating this! Kaname gives great careful pronunciation tips for long vowels, as well as the "n" ん mora and one more interesting facet of Japanese pronunciation: sokuon 促音, which gets transliterated as doubled consonants.

Doubled consonants, like in the set phrase いらっしゃいませ (irasshaimase, which is sort of like "welcome in": just a polite phrase people say when you have walked into a place of business where they are working—the set response it to not respond) are written out in hiragana with a small "tsu" っ and pronounced by preparing to say the consonant, pausing for a mora, and then continuing.

So in irasshaimase, you usually wind up pausing on a "sh" sound for a beat. And it really is a pause, you're not putting 100% force into producing the "sh" sound during that mora, but conversely you don't need to be completely silent for it either. There are lots of doubled consonants in Japanese, but somehow the first one that comes to mind as being borrowed into English is a little lewd.

Vowels

Vowels in Japanese are pretty straightforward:

- "a" is always like in "father"

- "i" is always like "ee" in "seek"

- "u" is approximately like "oo" in "boo", although you might try rounding your lips less

- "e" is always like in "bet"

- "o" is always like in "home"

Combination vowels are pretty guessable from the above, but:

- "ai" is like "i" in "design"

- "au" is a bit like "ou" in "outline" with a bit more "oo" at the end

- "ae" is also a bit like "design" but you turn it towards "eh" at the end instead

- "ao" also a bit like "ouch", but with more "oh" at the end

On the whole "i"-first dipthongs are less common and a little thought should be put into keeping them different from "y" sounds and "i-y" sounds. Like, "ia", "ya" and "iya" are three distinct sounds in Japanese. The middle one is one mora while the other two are two.

- "ia" is a bit like "heal"

- "iu" is a bit like "you"

- "ie" isn't super naturally occurring in English... maybe "yehhh" as a way of saying "yeah"?

- "io" is a bit like "yo"

The "u"-first dipthongs sound to me best pronounced as the Japanese "u" (which is a little different to English vowels but not exceptionally so) and then the next vowel.

- "ea" is a bit like "air" (indeed, in the loan word for "air conditioner", that's the sound that is used.)

- "ei" is a bit like English's "long a" sound in "wear" or "care". In Japanese pronunciation of Chinese syllables, "ei" often takes the place of what might otherwise be a doubled "e"

- "eu" is very uncommon, and it and "eo" are probably best approached as putting two sounds next to each other.

The dipthongs "oa" and "oe" sound like two sounds to me, although "feather boa" is pretty close.

- "oi" is like "boy"

- "ou" occurs extremely frequently (often in pronunciation of Chinese syllables) and it's more or less fine to treat as a long "o" sound. The Japanese pronunciation of "Tokyo" has two of these, for instance. I'm not aware of a pair of words where "oo" vs. "ou" is the distinguishing feature.

Syllabic "n"

Although not really a vowel "n" probably belongs here as well. The ん sound is the only one not allowed to begin a word. Probably your safest bet is to think of it a bit like an "ng" sound.

Some nuance: say "ring". Okay, now say it again, but when you get to the "ing" part, bring your tongue up like you probably did the first time, but this time leave it floating in your mouth rather than touching the roof. That's also a valid ん. When followed by a voiced consonant, leaning all the way to "m" is correct. A normal "n" sound like in the name "Shannon" is okay, but probably will sound a bit off in most cases.

Consonants

These are almost all straightforward. Here are a few things that jump out to me

- し "ought" to be "si" but it is "shi" because that's what you'll hear.

- ち and つ "ought" to be "ti" and "tu" but are "chi" and "tsu" again because that's what you'll hear. The "ts" sound is a bit like German "z" or as in "boots" but can occur in places in Japanese that it cannot in English

- ふ is a bit more like "fu" than "hu", but it's not quite as intense as the English "f" sound can be.

- を is almost never pronounced as "wo", but rather as "o" and almost always written out that way to be a "particle" (more on that later).

Japanese "r"

The one consonant sound that might give you some trouble is transliterated as "r". If you were to triangulate the space between English "r", "l" and weirdly "d", I think you'd find Japanese "r" somewhere in there. Say "read" and notice where your tongue is helping you produce that sound. It's probably pretty far back in your mouth. Now try "lead". There although it's a similar movement, your tongue might even be up at your teeth. Now say "deed". Notice that the motion of your tongue is a bit similar to "l", but that it's further back.

For Japanese "r", you basically want your tongue position around where it was for "deed" but then make a motion more similar to "r". For starters, try softening or avoiding contact between your tongue and the roof of your mouth. It's sometimes described as a "flap r" if that's a useful image. Whereas my English "r" for "real" is engaging a part of my tongue further back, my Japanese "r" is using more of the front part of my tongue for a similar, "flappy" motion. So it's not quite a rolled "r". And for me it does, especially if said quickly, accumulate enough quick motion to give it some of the effect of a "d" sound—it's a bit more ... "consonanty" than English "r" in that way.

Dropping sounds

The "u" sound and some "i" sounds are a bit weaker in pronunciation than other vowels, and are sometimes so weak that they're not really pronounced. The polite word for "to be", です (desu) for example, is really more pronounced as "dess". You might include a little "u" sound almost under your breath if you'd like, or drop it entirely. Pronouncing it fully sounds a little exaggerated and unnatural, which can be useful as an effect—one way to sound a little cute and girly might be to use です more frequently than is necessary and pronounce it by drawing out the timing of the "e" sound and giving a short but certainly audible "u" in the "su".

Pitch accent

Although Japanese isn't a tonal language, it uses pitch both for intonation in the context of a phrase or a sentence, as well as within a word. A great example of the sentence and phrase level intonation is the "thanks to our sponsors" message you used to hear in anime before streaming really took off.

As you can hear, the first phrase in the sentence is demarcated broadly by getting a "going up then going down" shape in pitch. Pitch is also used (similarly to in English) to make questions sound like questions.

Within a word, you might hear the same sort of movement: Kaname exaggerates this slightly in his pronunciation of ハンバーガー (hanbaagaa, "hamburger"), but a smaller version of the same "up and then down" shape sounds right to me. There are several pairs of words which are distinguished in spoken Japanese only by their customary pitch accent. A triple that stands out to me in the list at the bottom of this thorough explainer on pronunciation is 神/紙/髪, ("god", "paper" and "hair", respectively) all of which are "kami". The former has a "high to low" pitch accent, and the other two both have "low to high" pitch accent. (Indeed, I think those two are really pretty homophonous to my ears.)

"Katakana English"

Japanese has many loanwords from English. At the beginning of Kaname's video above, you can hear him say back an English word in "katakana English"—that is, in the way a Japanese speaker would parse the word into Japanese sounds.

The rules are pretty straightforward: take "McDonald('s)", the first word Kaname says.

- The "Mc" part also sometimes being "Mac" in Scottish is maybe one reason why you should choose 'a' as the vowel sound to pair with 'm' here. Also, Japanese doesn't really have a schwa (the unstressed, kinda muddy "uh" vowel sound you make all the time when speaking English), and 'a' is frequently the least energetic of the options, so it gets used a lot.

- We need a "k" sound and a "d" sound next, but in Japanese we cannot put them next to each other without an intervening vowel. In this situation, you should choose "u" if it is available to you (we'll see a case where it isn't in this word). So, "ku" and then "do"

- I hear the way the "l" is "colouring" the "a" at the end of this word, but that option isn't really available to me in Japanese without introducing a full "r" mora. Since we get a full "l" sound if we pronounce "McDonald's" fully, I agree that it makes sense to introduce an "r" mora, but in cases like "Harvard" where the "r" really is just colouring the vowel, Japanese will tend to just use a long vowel instead.

Another, more subtle case for introducing anything here in the word is that makes the word fit some of the Japanese patterns of speech. Without doing anything, we'd have a 5-mora word with five pretty high-intensity consonants back to back. Adding in a sixth mora that modulates between the "n" and the second "d" helps (subjectively) ease the pronunciation of the word a bit. The stress in English is before the "n", but somehow lengthening the "o" in "do" or even replacing it with "daa" doesn't really help release any tension in the word.

- Finally, to end the word, our instincts should tell us to reach for a "u" sound since we need a vowel after every consonant. But, "du" is unavailable to us in standard Japanese, so "do" is the next best option—this is pretty frequently the case with "t" and "d", like ロボット (robotto) for "robot". You could think probably defensibly about the apostrophe "s" being dropped from the word as "grammar" that Japanese doesn't translate.

All in all, we agree with Kaname: makudonarudo. Now it's your turn: How about "Mulholland Drive"? "Robbie Lyman"? "New York"?