How to Try Learning Japanese

Or: what I'm trying and have tried, anyway.

I think I was in middle school when I decided that I wanted to learn Japanese. I think the draw was some combination of anime (also Pokémon), sushi, a sense of interesting culture and history, and the difficulty of the language for English speakers.

I'm still not as fluent in Japanese as I would like to be. There is a proficiency test every December (and July in some countries) with five levels of proficiency available; I attempted the middle one this past year; I hope at the end of this week I'll hear that I passed it. In CEFR terms, this indicates somewhere between A2 and B1 level.

My goal is to be as proficient in Japanese as I am in English.

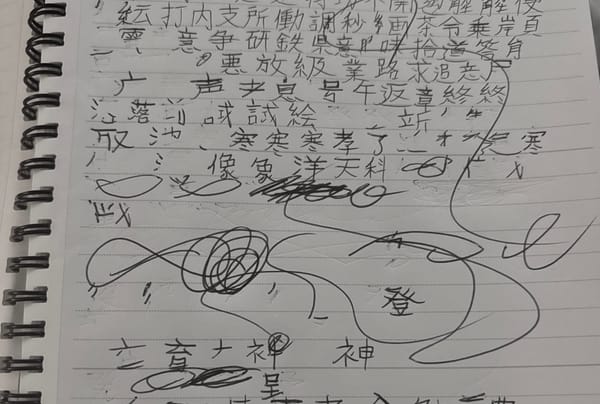

At the same time, I'm making progress. I can be expressive to the point of having flirted a little in Japanese. I have at least some knowledge of about 800 Chinese characters used in writing Japanese. Last year I read about 10 (very) short little books in Japanese and started reading manga in Japanese as well.

Anyway, I was asked about how one learns Japanese. I'm not sure, but I do know what I've done so far. So that's what this post is about. The first part is about how to reach the "four semesters" plateau. The end of the post is a brief overview of everything I've tried to push past that.

First: learn the sounds

In my previous post I talked at great length about the sounds of Japanese. There are not so many, and for an English speaker getting 80% of the way there is not difficult at all. Anything beyond that you can (and should) do by listening to spoken Japanese and trying to perform exactly how they say it.

I think I did this over the course of at most a couple days, in middle school. (I think I had heard some of the thought in linguistics that as people age they lose the ability to distinguish phonemes. I think personally that this is probably bunk—as in, I believe your ability to learn anything probably goes away only when you are dead—although I don't deny that it gets more difficult to notice something that hasn't been meaningful in your understanding of speech.)

Second: learn Hiragana (and Katakana)

Of the three Japanese writing systems, learning kanji is the most difficult, and learning hiragana the easiest. Learning hiragana can be begun in one sitting and probably only takes a couple days to a week to have well in hand.

I remember sometimes practicing while bored in class in high school and (less frequently) college by writing out the "fifty-sounds" table of hiragana. At the time I found it difficult to remember the order that the consonant sounds are "supposed" to go in. Since I'm fairly frequently interacting with the Japanese keyboard on my phone, this has gotten much easier.

I didn't really use mnemonics to remember hiragana or katakana, but also I was pretty motivated and young. If you're on board the mnemonics train (it's a great train), Tofugu has a great guide.

Digression: Japanese Writing

Yes, Japanese has not just one but three more or less complete writing systems: hiragana, katakana and kanji. Idiomatic Japanese writing makes fluent use of all three; it's not uncommon to see all three in a single sentence, or even in a single phrase.

Kanji

The oldest of the three are the kanji (漢字, lit. "Chinese (Han) characters"). These are, as the word implies, characters historically taken from Chinese. Some differences have accumulated since the borrowing, basically because two different cultures have stewarded their use and orthography. For example, in "simplified" Chinese characters, one would write 汉字 instead of 漢字. I believe some simplifications of Japanese kanji exist which don't happen in "traditional" Chinese characters. Additionally, some kanji are made in Japan by combining elements of other kanji in a way not found in Chinese.

There are thousands of kanji. The Japanese government maintains a list of a little over 2000 jouyou kanji (常用漢字). These are the kanji allowed in official government documents, and Japanese schoolchildren are taught all of them. However, not all of the jouyou kanji are truly jouyou (meaning "normal use"); not all of the 2,000 most commonly used kanji in newspapers are jouyou. For example, 舐める ("to lick") uses a non-jouyou kanji.

Chinese characters are sometimes described as "ideograms": although sometimes in Japanese (and I imagine in Chinese as well) they are used for sonic value alone, usually they are used to convey both meaning and sound. The characters in 常用, for instance, have some of the sense of "normal" and "use" in every appearance, respectively. The former, for instance, appears in 日常, nichijou, meaning "everyday" (also the title of a quintessentially "slice of life" anime and manga series), and the latter in 用事, youji, meaning "chore".

Hiragana + Katakana

Both of the other writing systems are less complex. While not alphabets, they are syllabaries, allowing you to write all of the sounds of Japanese.

Both hiragana and katakana have their origins in kanji: hiragana are usually thought of as a formalized system of cursive shorthands for kanji. This explains their more curvy appearance, like the last two characters we saw above in 舐める. Kanji, you'll quickly notice if you pay attention, have no round circles. While curves do occur, these occurrences are pretty regimented. Katakana, on the other hand, are not so much cursive shorthands as synecdoches for kanji. The katakana character カ, for instance, is a part of, for instance, the kanji 加, which it shares a sound with in many readings. (Confusingly, there is also the kanji 力.)

Why not just kanji?

Linguistically, it turns out, Chinese and Japanese are pretty different. Chinese is very well-suited to being written in Chinese characters: my understanding is that there isn't much in the way of conjugation (things like English "do/does/doing/did") and Chinese for the most part doesn't go in for mashing up bits of other words German-style.

Japanese makes the opposite choice on both of these fronts. Consider the sentence 見に来てくれなかったんです ("mi ni kite kurenakatta n desu"). This means roughly "it's just that you didn't give me the gift of coming to see X", although "you" is understood, X is left unspecified, and the phrase "it's just that" is a rough attempt at translating the "splainin vibe" that the sentence has as a result of the んです at the end. There are only two kanji in this sentence (見 and 来, which suggest "see" and "come", respectively), more or less because everything else is subject to conjugation, changing "see" and "come" into "come to see", for instance, and "(you) give" to "(you) didn't give", adding the splainin vibe, and then making the whole thing a bit more polite.

In short, having kanji alone would make it difficult for Japanese to communicate some of its linguistic expressiveness.

The above sentence, though, makes use of no katakana. Of the three systems, katakana occur least often. They have some of the vibe of italics in English: they can give a sense of emphasis, and can also mark foreign words. I write my name in Japanese as ロッビー・ライマン ("robbii raiman"—recall that there's no distinction between L and R) for instance.

Having katakana available adds to the expressivity of written Japanese. As an example, the manga Polar Bear Café uses katakana to great effect in a story where one of the characters (Mr. Penguin) is complaining to another (Panda) about his struggles obtaining a driver's license. (Speech bubbles in manga are usually implicitly ordered up to down and then right to left)

The word "parallel parking" (縦列駐車) is written out in katakana "phonetically" as ジューレツチューシャ ("juuretsu chuusha"). Polar Bear Café has a repeated gag of "puns" where a character (often willfully) slightly mishears a phrase to comic effect. In this chapter, though, the next page has Panda lost in thought trying to figure out what ジューレツチューシャ could possibly mean:

In this case, alas, I wasl also the butt of the joke: like Panda, I couldn't figure out "parallel parking" just from the sounds, and I think my first guesses would also have mistaken 縦 for its homophone 十, meaning "ten".

Bonus: learn katakana and kanji stroke order

Learning katakana and hiragana at the same time is totally doable; I recommend. It's okay if katakana get less of your focus and take a bit longer to feel familiar; they come up a bit less frequently.

The stroke order rules for kanji are very sensible: most strokes travel left to right and up to down. Strokes that don't are and should be also visually different from those that do. For example in the uncommon kanji but common radical 禾, the odd stroke out is the very top one: it indicates that it wants to be written from right to left by also being slanted.

The stroke order for kanji are also broadly: top to down, left to right, out to in. There are a couple cases where one kanji makes one choice and another the opposite one, (the part common to 右 "right" and 左 "left", for example) but for the most part, once you've learned how to write a component of a kanji, every kanji using that component will write it the same way, so there aren't so many times you'll find yourself second-guessing the intuition you build up.

There are many people out there who will tell you that learning to write Japanese neatly on paper with pen or pencil is useless. While you can probably get away with only ever typing, I think this is a sad way to live. Also, it happens not infrequently to me that I know how to write (i.e. draw) a character but not how it sounds. In order to look it up, then, a great option is to be able to handwrite the character into an app. Knowing the correct stroke order for doing this will only help the computer help you do that.

Third: learn Grammar

When I was in middle school, I was gifted an older Japanese textbook which was fully written in romaji (that is, Roman letters). This made picking apart some aspects of Japanese grammar incredibly simple.

I don't recommend this. Grammar is very cool, especially if you, like me, love the sort of system which follows a pattern but only somewhat. But in the way that if I were to ask you whether and how this sentence uses the subjunctive mood, you might not be able to answer me unless you 1) learned English as a second language or 2) studied a language which also has a subjunctive mood, so too is grammar ultimately best when not learned so much as breathed.

That being said, I cannot resist nerding out.

Grammar

Japanese's sentences are structured as "topic comment" or "subject object verb" rather than English's "subject verb object". The grammatical role a word plays in a sentence is indicated by little "particles" which are a bit like English's prepositions, but they come after the relevant word. Many parts of a sentence may be omitted if understood in the way that in English we use pronouns instead of restating what "it" means every sentence. Actually, arguably Japanese does not have pronouns.

The topic and grammatical subject of a sentence are often identical, but they may be distinct. Word order is also (thanks to particles) fairly flexible. Modifiers like clauses and adjectives always come before what they modify, but verbs tend to accumulate conjugation and other cruft at the end.

Japanese has the following parts of speech:

- Nouns (名詞), which do not conjugate and mostly do not distinguish between singular and plural

- Verbs (動詞), which conjugate according to tense, politeness, active/passive/"causative"/"causitive-passive" and a couple of other ways which I guess you might call "mood" like in German, but is really its own thing, and all of which except I guess "to be" are listed in the dictionary as ending in "u". Verbs can be transitive (他動詞) or intransitive (自動詞), and many verbs have a variant of both flavors.

- Adjectives (形容詞), which conjugate and are a bit like verbs, and all of which end in "i", and are therefore often called "i-adjectives" in English

- uhhhhh, Different Adjectives (形容動詞), which do not conjugate and are more like nouns and take "na" when modifying things, so are often called "na-adjectives" in English. (Confusingly if you're paying attention to the Japanese, 形容動詞 is a mashup of the word for adjective and the word for verb)

- Particles (助詞), which come after what they modify

- and ... everything else, which are mostly called "Adverbs" (副詞, kinda "side word") in English.

How to learn Grammar

I tried self-study initially, and did so-so. The romaji textbook taught me the basics such that when I took a class (which, spoiler, I'm going to recommend to you in a second), it was maybe a couple semesters in before I got to learn something I hadn't already seen.

In grad school, after having passed my quals, I realized two things: one, I was starving for quicker feedback and more visible progression than research was likely to give me. Two, my tuition was already covered. So I took four semesters of Japanese. I highly recommend taking a class at some point. You get dedicated time and accountability, and more practice speaking and generating written work than you are likely to give yourself at the beginning.

I took another class for adult learners this past semester on Zoom through the Japan Society. If a class and a weekly time commitment are in your budget but there aren't classes held physically near you, I'd recommend.

For me, sitting on Zoom for three hours after a frequently draining day (for me both class and therapy were on Thursdays) was not nearly as great as being physically present with my fellow students (even though they were much younger than me) in grad school. I also don't know that (by the end of the semester) I really needed a class, per se, as much as dedicated practice time. Also, if the class is taught out of a good textbook, it will correctly push you to take responsibility for kanji early in the process.

If you don't take a class, I still did get a lot out of the textbook series we used, Genki I and II. I'd recommend; the textbook is legible, and it strikes a nice balance of introducing grammar and kanji at a decent pace.

After the intermediate plateau

Another way to title this section is: "you took four semesters: now what?" I've tried a bunch of things—not everything out there, but a bunch. Here's what I think of them.

- Duolingo: I don't hate it, but as a singular study device, Duolingo is not good. It is responsive to you demonstrating increased competence in the language, and having "finished" the course (which at the time of writing caps out at a "Duolingo score" for me of 100, far lower than their max of 160 for some other courses), I can say that some interesting sentences and vocab are hiding in there somewhere. Annoyingly, it happens not infrequently for example that the voice line and furigana indications of pronunciation will disagree.

- Anki: It's ok. I tried "mining" every word I had to look up while reading Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba, and I think that was unsuccessful because that's a silly way to study. I've been building a deck asking me to practice writing a kanji based on a keyword I took from WaniKani (more about below), and I think that's been somewhat useful, although I think probably the wrong kind of practice ultimately.

- LingQ: It's ok. I think the core idea is appealing to me: I learned a great deal of my skill with English by doing a lot of reading and listening to English. I think the platform ultimately doesn't make a lot of sense: it's neat that they somehow(?) have aggregated a bunch of content both native and meant for learners, but the reader interface is clunky, and the definitions suggested for words are sometimes AI slop. If you're serious about trying to learn via immersion, probably you want to go more "to the source" anyway.

- Jumping right in to reading: It's ok. I read the first two or three volumes of Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba with a dictionary right next to me. It was not particularly pleasant, but it worked. I think this is fine, but it's not really practicing reading so much as translating. Granted, I'm not sure my vocabulary and skill at reading was enough to do anything else.

- WaniKani: This is fantastic. Their "moat" is extremely low. The basic idea appears many times in English; Heisig's Remembering the Kanji takes perhaps the most intense approach to it. Basically their claim is: to learn a kanji, you should create a mnemonic story that connects its components (which WaniKani collects somewhat arbitrarily into "radicals" and gives you names for) and readings together. To learn a word, you should also use this process. They have provided an app that collects ~2000 kanji and ~6,500 vocab words into 60 levels and feeds them to you at a maximum rate of one level every week.

- Tadoku Graded Readers: This is fantastic. This was maybe the first time I read a whole multi-page story in Japanese and was like "wow, I understood that whole thing, even the couple words that were new to me".

- I heard about the graded readers through WaniKani's fantastic forums, which if you're a forums person are pretty lovely to hang out on. If you like posting somewhere for accountability, they have that for you. If you want to join an asynchronous book club, they have many.

- Watching anime with subtitles: It's mid. I mean, don't get me wrong, I love anime. But you're not getting much Japanese learning in if you're watching with subtitles, because you're focusing on reading the subtitles while also watching the action.

- Listen or watch the same thing over and over: to be honest, I'm still a little shocked at how effective this is. I got this idea from Days and Words, a YouTuber. He suggests that you should pick about an hour of content—preferably an audiobook—and just listen to that about once every day for a month and then rinse and repeat.

Wait what?

Yes, just listen over and over and you'll weirdly start to get more and more. I mean, it helps if you 1) like the thing already, maybe because 2) it's a translation of something you know (or it's an anime you watched already with subtitles)—that will help with high level comprehension at the start too, and 3) you have access to a text form of (most of) the words too, so that you can pick out sentences to translate if you get stuck.

I've been listening to the same two chapters of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (ハリー・ポッターと賢者の石) and the same two episodes of the Death Note anime for about a month.

(I'm not a particular fan of J.K. Rowling's forays into being a public figure, to put it mildly, but I think I would be hard-pressed to find a comparable book for me to use as a language-learning tool.)

I found Days and Words kind of by algorithm after watching this incredibly inspiring interview he does with a Norwegian learner. One of the things I love most about what she says in that video is the idea of "wow, this task is so big and seems like it'll take impossibly long—let's get started!" The "comprehensible input" idea and repetition are both pretty popular in a certain segment of the language learning internet, so I figured I'd give it a proper go.

You'll often hear in those contexts that it's important to be comfortable with ambiguity, and with not getting it, and I think those things are true. But also that actually that advice is backwards: you'll get more comfortable with not fully knowing what you're hearing by practicing. You should just practice.