Surely! He Hath Borne our Griefs

I just clocked that like "Panic" or "Godspeed", "Surely" is two syllables long and takes to a cheeky little exclamation point like a duck to water.

I was wasting a man's time the other day and mentioned I was going to see Handel's Messiah and he was like "what's that," which was not surprising to me given what I knew of him. I never really know how much to assume that people know about a thing when I tell them about it, but I think this seems like permission to tell you everything.

Messiah the music

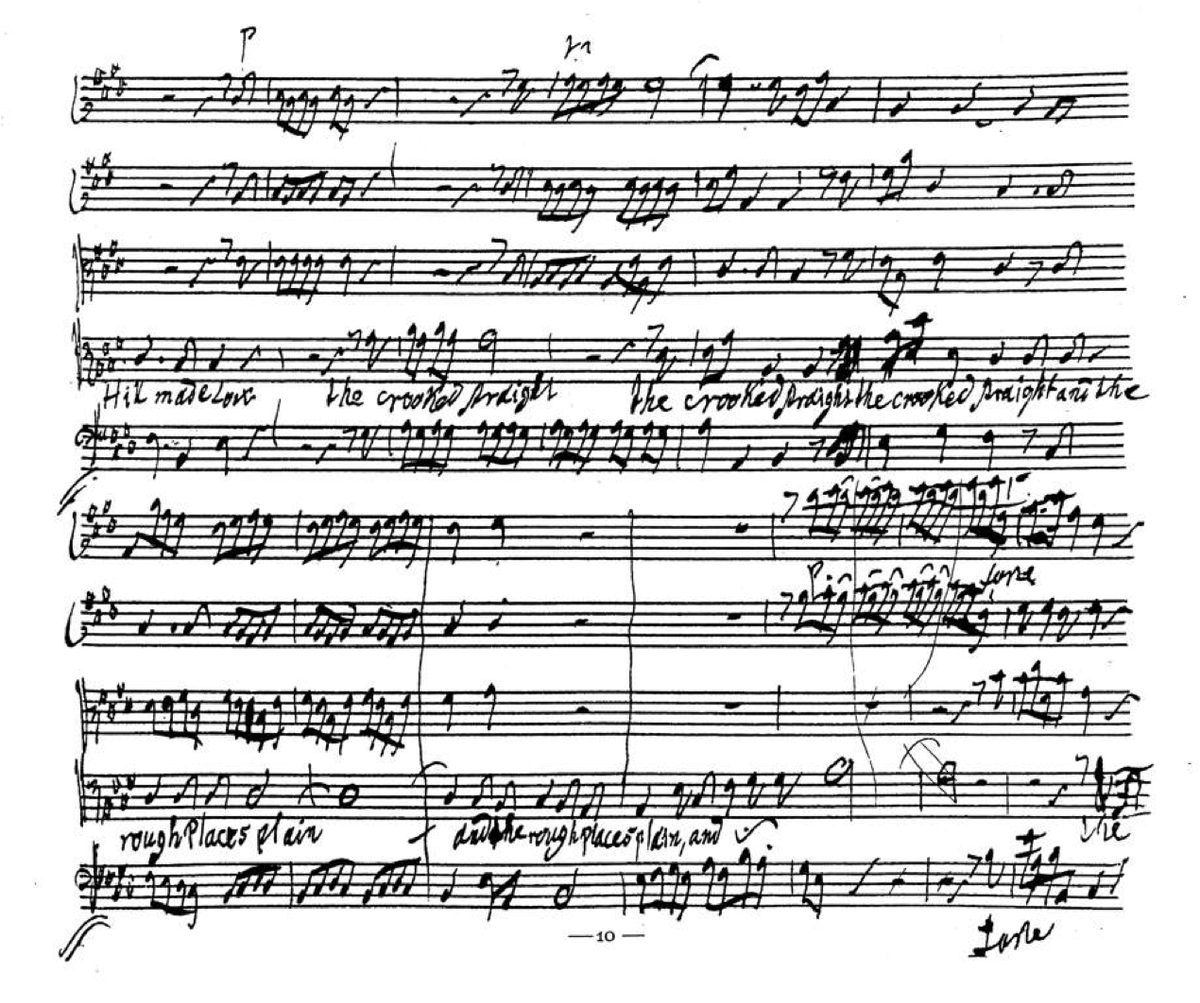

Georg Friedric Handel composed Messiah in, apparently, 24 days nearly three hundred years ago. The handwritten orchestration (screenshotted above) runs to more than 250 pages, meaning our boy was cranking out at least ten pages a day. Apparently the librettist found this careless.

The whole oratorio (his sixth in English) has about 53 tunes, and Georg really packed these pieces full of riffs. "Hallelujah" is likely the most famous, and it's customary to stand when it is performed, but if you're new to Messiah, I'd recommend "Every valley", "The people that walked in darkness", "And he shall purify", "All we like sheep" and "He trusted in God" as pieces to check out first.

The pieces are split, like in operas of the time, between "arias" and "recitatives"—although many of the arias feature a choir, rather than a soloist. Arias are in many ways the precursor of the modern pop song: they often have repeated, catchy motifs and whole sections that are sung multiple times. Recitatives (certainly in Messiah) often have minimal accompaniment, are somewhat less strictly timed, sung through basically once, and serve mostly to convey text that situates the coming music in relation to what came before.

What I most love about Messiah, musically, is the sense of angular motion, ticking. Especially when performed just this side of rushing it, as more performances I've seen tend to do than not, you really get the sense that the orchestra is this little machine that is here to absolutely shred riffs. "The people that walked in darkness" is perhaps the aria that most brings that sense of corners and angles into the vocal line, although the piece is on the whole a bit more stately in tone and tempo than "He trusted in God", which almost functions like a Baroque invention, setting the four divisions of the choir against each other to use the main motif against itself, revealing harmonies and counterpoint in a round.

Twelve years a Countertenor

I've seen a performance of Messiah nearly every year for the past 12 or so. I forget if it was my mom or an ex who started my going as an adult, but lately it's something I look forward to doing with my mom and whoever else wants to tag along. Twelve years ago, I remember feeling that having a countertenor perform the alto solo pieces was surprising, subversive maybe even. I think, in fact, though, that I might have seen more countertenor performances than performances with an alto.

In college, one of my favorite college courses was a year long music theory sequence I took with Ramin Amir Arjomand on the strength of the polarized reviews I heard about his style. We spent a good amount of time in class, for example, marinating in an achingly slow I-ii-V-I cadence and trying to tap into the feeling the V chord produces. Many of our homework assignments were to write little four-part harmony progressions, some of which we would sing together in later sessions. I remember feeling smug about getting to sing the alto part.

Speaking of feelings, over the past two or so years, I've been surprised to discover a fairly constant embodied sense of emotion that I fail to find in my memories of my 20s. Last fall, for instance, I spent a couple weeks perplexed about a small, concentrated ache in my chest. Like, to the point where I almost became concerned that this was a physical symptom of something wrong with my physical chest, not a location for a feeling.

I ran through many hypotheses about what that feeling last fall might mean. These hypotheses, even if correct, do very little to move the feeling, which is uncomfortable. More recently I realized that the feeling wants to be felt. Several feelings can wind up manifesting as this sort of heart pain. For me, what seems to be common to them is that the feeling is difficult to acknowledge.

Seeing Messiah this year, that sense of unacknowledged feeling arose again. Not so much provoked by the string players, although it would be nice to be able to play the violin. More so the woman in the choir whom I knew in high school and haven't really spoken with since. The countertenor, the tenor, even the bass and the soprano.

I felt jealous.

Actually, maybe every concert I've been to since the Sweat Tour has provoked some amount of jealousy. I remember sitting in the stands at Madison Square Garden, realizing that Charli and Troye were putting on a good show as far as theatrics, dancing, lip synching and singing, but one that I absolutely could put in the time to put on myself. I've psyched myself out of attending a couple concerts more or less alone over the past year, partly (I wonder) because of the discomfort of wanting to be on stage.

If you want to start a band, let me know.

Julia Tap-Dancing Cameron

Anyway, so there I was, doing this sort of interoception. Even though I've, uhhh, felt jealousy a large number of times over the past year, when it presents this way, it still takes me a bit to figure out that I have to feel whatever is causing the chest-pain feeling.

The way forward from the feeling isn't so difficult to suddenly-I-see: this is what I wanna be. Suddenly I see, why the hell it means so much to me. That's hardly a revelation to me.

In a parallel castle, NCFDD advises faculty to write (very broadly construed) for 30 minutes every workday as a bit of a panacea for the woes of faculty life. Certainly, I have found that when I am touching my research daily, I have less angst and jealousy about what my friends and foes in math are up to. With the end of the semester looming, I put this writing habit into my lifeboat, but didn't put Ableton Live in alongside it. Now that the semester is over, I'm surprised to find that I have a bit more work to do than just say "open Ableton" and jump in.

Or, I suppose "surprised" is not really the right word. Dismayed, I suppose, that I am not a little puppet that can be ordered about and dragged through every difficult or distasteful-seeming task that is on my plate.

Over the summer, a motley band of six friends scattered across the US worked through The Artist's Way together.

Recently we were chatting about our surprise to discover that we were part of a trend! Bookstores each of us are connected with continue to post it as one of their books of the year. In my Discord, a reel mocking The Artist's Way—in the extremely deep, "we read the whole thing at least twice" way that you only really can if it aimed for your heart and came really close—was shared twice. I didn't like the reel at all. (To be clear, I don't think I really was supposed to; it's in the vein of reels classics like "POV: you work at a charity nonprofit and your boss is about to ask you to work over Christmas".)

Personally, I dunno that "5 ethnic neighborhoods (this is actually in the book)" really puts the screws to a book published in 1992, you know?

Julia's core method is very simple: write three pages every morning, and take yourself on a date every week. Each of the 12 weeks she talks through an aspect of creative block that might resonate with readers of her book. I was surprised, for instance, at how loudly money (practicality, expense, living within one's means) turned out to be clamoring for me. I expected to be castigated for my attitudes towards sex and relationships as a vice, but instead I appear to have done more than enough to make myself feel bad about that. (So I'm trying to not feel bad, for instance, about the enjoyable aspects of wasting the man at the beginning of this post's time.)

She also talks a lot about God.

She asks about the ways we use God and all the accoutrements of religion as a hairshirt, as a flog. And she asks what it would be like if instead of all that, we hold onto the parts of our God stories that have God as something that is waiting for us to ask for help in order to provide us with it.

Early in the book she suggests that you adopt some affirmations that you can use in the pages if they feel helpful. A less frequent one for me, but a powerful one is to write "I know that God loves me, like he [she] loves all artists". (I grew up Mormon, so "He" for God feels most natural, but I am not attached to a belief in, a gender for, or even a personification of God. Lately I feel aligned with Buddhism, but I feel keenly that I don't know much about it at all.)

Surely!

Anyway, all of that came to mind as I'm sitting there interocepting in the middle of Messiah. And "Surely" comes along, harmonizing nicely with my thought process. "Surely! He Hath Borne our Griefs" comes, in the recording I happen to be listening to right now, after an eleven minute track, "He was despised". I'm not sure if that track is an aria with a recitative in between? But it's a clear outlier in length.

"Surely", by contrast, is a fairly short choral piece, but I was struck, listening to it, that this usage of the word "surely" in the King James Version of the Bible (Isaiah 53:4) and its setting to music in this piece have surely contributed noticeably to the colour the word has in ordinary English usage.

Here are the verses in the King James Version of Isaiah the text (bolded) is drawn from.

Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows: yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted. But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed.

The opening word, "surely," is repeated immediately and the first phrase as a whole is repeated, but when the song later revisits the staccato theme that opens the piece, the rest of the section ("the chastisement") of Isaiah is inserted instead, and the piece is finished.

This approach to form isn't uncommon in the Messiah for many of the arias and choral pieces, and probably would work pretty well on the radio today with the recent microtrend towards shorter songs. Unlike most of the choral pieces, however, the choir enters both all together and pretty loud. Keeping with the pop song theme, I guess you'd say it jumps straight into the chorus.

I hope whatever recording you have found to listen to the piece adequately gives you a delivery of the word that you could really hold in your hands. In the next songs, the mood lightens to discuss the results of Jesus bearing our griefs and being bruised for our iniquities, but in this one the weight of that work is really present.

I think I'm still not sure how to square all this. I tried to find fault with the joyful mood of "And with his stripes we are healed" in an earlier draft, but doing so actually needs you to put feelings into Jesus that don't square with his characterization.

How do you accept a gift you can never repay? Why is it difficult to say just say "thank you, I ... know it pleases you to give the help I ask for, and I will try to feel I deserve the help"?

Somehow I don't think belittling the desire to be a comedia dell'arte clown is the answer, but maybe that's just me.